Liberalism has always had its critics. A political tradition that classically has defended certain freedoms (such as the freedom of speech and freedom of religion), and has been strongly tied to free market economics was always going to attract enemies.

Since the Second World War that critique has increasingly morphed into a critique on the whole modern project. Since the early 2000s, a trend emerged in conservative and Christian circles postulating the end of liberalism altogether. The term ‘post-liberal’ may have first been used by British philosopher John Gray as early as 1993 is his book: Post-Liberalism: Studies in Political Thought. Gray ran an early version of the argument that neoliberalism undermines itself through globalisation and an unfettered markets; points that were briefly adopted by Tony Blair in his Third Way before New Labour reconciled themselves with neoliberalism.

It was in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis that theorists in both the US and the UK started to advocate for the end of liberalism as it had developed in the late 20th and early 21st century. These augurs of liberalism’s demise argued that forces had been unleashed by liberalism which, when combined with inherent contradictions within liberalism, meant that the end was nigh.

Though their most stinging charge was that liberalism itself had become a threat to liberal values. Liberalism had betrayed itself":

‘Nearly every one of the promises that were made by the architects and creators of liberalism has been shattered…The only rights that seem secure today belong to those with sufficient wealth and postition to protect them, and their autonomy—including rights of property, the franchise and it concomitant control over representative institutions, religious liberty, free speech, and security in one’s papers and abode—is increasingly compromised by legal intent or technological fait accompli.’1

What was needed was to start envisioning the post-liberal world.

These critics, such as political scientist Patrick Deneen and journalist Rod Dreher in the US, and theologians John Milbank and Adrian Pabst in the UK, tended to have a Roman Catholic or Anglo-Catholic background, and tended to be influenced by catholic social teaching. What is perceptible is the influence of those earlier critics of modernity on the Post-liberal theorists, such as Alasdair MacIntyre, the former Marxist turned Roman Catholic who argued in After Virtue that late modernity has inherited traditions, symbols, and institutions of which we know nothing about.2 We are the barbarians, so to speak, standing in the ruins of Rome and not knowing what to do. What the world needed argued MacIntyre, was ‘another Benedict’, that is another Benedict of Nursia, who established the Rule, which attempted to arrest a decline in virtue and became the foundation of monasticism in the Latin church, and formed a monastic community.3 On MacIntyre and later Dreher’s account, Benedict’s community became the Noah’s Ark which saved both the faith and western culture as Rome fell to the barbarians.

The post-liberals could recite a long litany of failures which would inevitably doom liberalism. These included:

an increased peril to free speech with the rise of a seeming intolerant progressivism in politics that sought to control speech and punished those who did not conform.

the continued growth of big government coupled with the rise of surveillance capitalism which increased the footprint of the government into more and more areas of life with the ability to monitor every careless word and keystroke.

a seemingly distant ruling class that appeared out of touch with society’s needs. While liberalism originally claimed to replace distant and arbitrary rule with popularly elected representatives, the growth of government necessitated a growth in the bureaucracy, staff increasingly by technocrats who seemed faceless and unaccountable.

increasing income inequality produced by a free market has created social fragmentation and increasing economic stratification in western societies. To manage this, post-liberal theorists argue that the state has continued to expand in order to deliver more and more services to people in society, thus creating an overbearing state apparatus. At the same time, the widening gulf between rich and poor has been increasingly protected by liberal states which have protected the prosperity of the wealthy in the name of the free market.

a belittling of classic means for human flourishing as family, community, and tradition in the face of a hyper-individualism which is premised on the maximising of choice but in the end alienates individuals from their social bonds to such a degree that humans became (at best) merely autonomous agents, or (at worst) consumers to be preyed upon by the data-collecting multinationals and tech giants of late modern capitalism.

the rise of hyper-individualism leaves society unstable because there is no shared commitment to the common good. Instead of a shared vision of the good, late liberalism has pursued a neutrality around personal values, refusing to comment values, beliefs, or commitments. Post-liberal theorists would argue that this neutrality is a myth, as even late liberal states have commended certain habits and beliefs. Some of the critics of liberalism would consider diversity, and migration as the greatest threat to social order and confusion, as a pluralistic society is a confused society.

a globalization which ignores the responsibilities to the local and the national. Liberalism’s globalist outlook is undergirded by ideological expansionism, particularly American imperialism, which seeks to proselytize non-western countries at the expense of local and national concerns.

a licentiousness in which every taste, every desire is permissible, making it impossible to form virtue. If free market capitalism has been the school of moral formation, then almost nothing can resist the right to exercise choice whenever or however you want.

From this list of complaints against liberalism you may be able to surmise that post-liberalism is communitarian in its approach to economics and social-polity, localist in its privileging of immediate community, and economic nationalist in prioritizing government intervention through tariffs and other means to support the national economy over the global. Post-liberals particularly pointed to the failure of liberalism to support communities after industry was shipped off-shore. Communities were powerless when work disappeared, and young people left never to return. What was lost was not just economic goods like work but an entire moral ecology of community, shared values and patriotism – for some the idea of work, family, faith and flag. It was argued that liberalism offered liberty and excess without values.

It’s worth noting however that there are significant differences on both sides of the Atlantic. Dreher and Deneen are both associated with conservative American politics; John Milbank is a little bit more eccentric to place. He has a high degree of incredulity towards the social sciences and their compatibility with Christian theology (an incredulity expressed through the radical orthodoxy movement which Milbank helped found and is again critical of modernity). And Milbank is associated the Blue Labour movement in British politics, seeks to promote culturally conservative values while remaining committed to labour rights and left-wing economic policies. Other British post-liberals, such as Milbank’s former student Philip Blond, are connected with the Red Tory political movement which proposes a communitarian traditionalist conservatism that inveighed against both state and market monopoly.

If liberalism is headed for its death throes, what should arise in its place?

That’s not quite the question Dreher sets out to address in The Benedict Option. Instead, he seeks to prepare the church to be ready to serve the world when the liberal order collapses. For there is a ‘great flood’ coming, and if Christians are not prepared, they will be swept away. What Dreher sees as rampant progressive liberalism entails a loss of influence and power for the church. So now is the time for a strategic retreat; withdraw and make ready. Taking as his guide first St Benedict, and second his new found home in Eastern Orthodoxy, Dreher argues that now is absolutely the moment for the church to take catechesis seriously. The church needs to be the church (another connection with Hauerwas’ writing), and deploy rich spiritual habits, liturgy, and support Christian culture making through art, music, and writing, in order to counter the strong counter-formation catechesis of the secular modern world. Dreher argues that the church must make disciples of its own people otherwise the world will do it. Theology and doctrine, the story of the saints, and an ethics that considers and celebrates what makes humans flourish, all of these are necessary if the church is going to withstand the cultural pressures of late secularism.

Christians must do this in community if they are to ride out the ‘storm’ that will crash when liberalism falls. In many ways what Dreher proposes in inspiring. What Dreher sets out is what church should be in the business of doing anyway for the purposes of discipleship. Though you can’t help but think that in setting an agenda for counter-culture building in preparing for societal collapse, Dreher’s proposal is largely a vision of monasticism, albeit fitted for the 21st century.

This is not just about our own survival. If we are going to be for the world as Christ meant for us to be, we are going to have to spend more time away from the world, in deep prayer and substantial spiritual training—just as Jesus retreated to the desert to pray before ministering to the people. We cannot give the world what we do not have. If the ancient Hebrews had been assimilated by the culture of Babylon, it would have ceased being a light to the world. So it is with the church.4

Where Dreher seeks to prepare the church, Patrick Deneen does attempt an end of his book to divine a way forward for what might follow liberalism. The 2018 publication of Why Liberalism Failed came with quick impact. It was blurbed by unsurprising sources: David Brooks and Ross Douthat of the New York Times, and Rod Dreher. But it was also blurbed by former American president, Barack Obama, who wrote ‘Why Liberalism Failed offers cogent insights into the loss of meaning and community that many in the west fell, issues that liberal democracies ignore at their own peril.’

Deneen argues that liberalism has failed because it was succesful.5 As a 500 year old experiment, liberalism has produced a political economy which depends on citizens behaving as just individualistic agents without character. Community, nature, and virtue are swept aside by a kind of hubris, as liberalism seeks to eradicate all limits. Meanwhile liberalism has become too caught up in ideological fights; having seen off first fascism and then communism, liberalism is pre-disposed to see things through the lens of ideological conflict which increasingly leaves it out of touch with the lived reality of its citizens. The constant tension between the government and the market, and the loss of purpose for society caused by the rise of autonomous agents with no shared vision of the good, leaves liberalism vulnerable to collapse by being unable to deliver what it promises. A theme that Deneen keeps returning to throughout the book, echoing Macintyre, is that we have a social order that no longer supports the cultivation of virtue in community.

So where to next? This is arguably the weakest part of the book. After the thorough critique, Deneen does not offer any concrete answers. No institutions are redeemed. What he proposes instead is threefold:6

Acknowledging the achievements of liberalism; there can be no going back to a ‘preliberal age’. Instead, post-liberalism must be built on the gains of the liberal order. What these are exactly Deneen never quite spells out, and his long critique of liberalism is only ever engaged in negative critique.

Post-liberalism must move beyond liberal ideological conflict and engage instead in the habits of the local: ‘we should focus on developing practices that foster new forms of culture, household economics, and polis life.’ Again, what this might look like is left unsaid.

And finally, what must emerge is a better theory of politics and society. Deneen suggests that this would be guided by liberalism’s demands for justice and dignity, and the pre-liberal concept of liberty. Again, this point is a little vague and repetitive.

A little later Deneen commends The Benedict Option for envisioning a count culture which is virtuous and local:

‘The building up of practices of care, patience, humility, reverence, respect, and modesty…seeking within households and local communities and marketplaces to rediscover old practices, and create new one, that foster new forms of culture that liberalism others seeks to obliterate.’7

While Deneen seeks to build a ‘liberty after liberalism’ he also warns against what may be provoked by the rise of post-liberalism.8 On the one hand, liberalism may respond with a despotic democracy such as Alexis de Tocqueville forewarned in the 19th century. Liberalism might seek to impose it’s vision of justice, tolerance, peace, opportunity, and equality by fiat, added and abetted by an efficient but distant bureaucracy. On the other hand, Deneen offers a caution that a plausible scenario would be the generation of a ‘populist nationalist authoritarianism or military autocracy’. The fate of the Weimar Republic and Russia’s 1917 Provisional Government make it a likely possibility for Deneen. Neither, he says, is to be wished for.9

Yet both despotic democracy and authoritarian autocracy are perhaps realistic outcomes because of the lack of alternative. Deneen blames the decline of liberalism on its advocates who are blinded to the peril liberalism is in. But the lack of constructive critique by a champion of liberty must also imperil liberty. Those who would deconstruct liberalism in the name of liberty without offering the blueprints of what comes next must content themselves with that liberty itself might be lost in the process.

Why post-liberalism outside of America hasn’t taken the same turn must be an area for reflection. In the Commonwealth, scholars as diverse as those mentioned previously (Milbank, Pabst), plus Oliver O’Donovan, Rowan Williams, Luke Bretherton, and Joel Harrison have posited a political order that is based on the common good. One that maintains the rights of individuals while seeking to promote community. Where the state nurtures what is already nourishing in society.10

The American post-liberals now find themselves proximate to power and influence. Rod Dreher now finds himself ensconced in Viktor Orbán court in Hungary. Following some horrendous years for Dreher, which culminated in the ending of his marriage, Dreher relocated to Budapest, where he is now a paid fellow of a conservative think tank funded by Orbán’s government. Despite describing himself as post-liberal, critics of Victor Orbán and his government would describe him as authoritarian and Dreher has become one of his staunchest English speaking apologists.

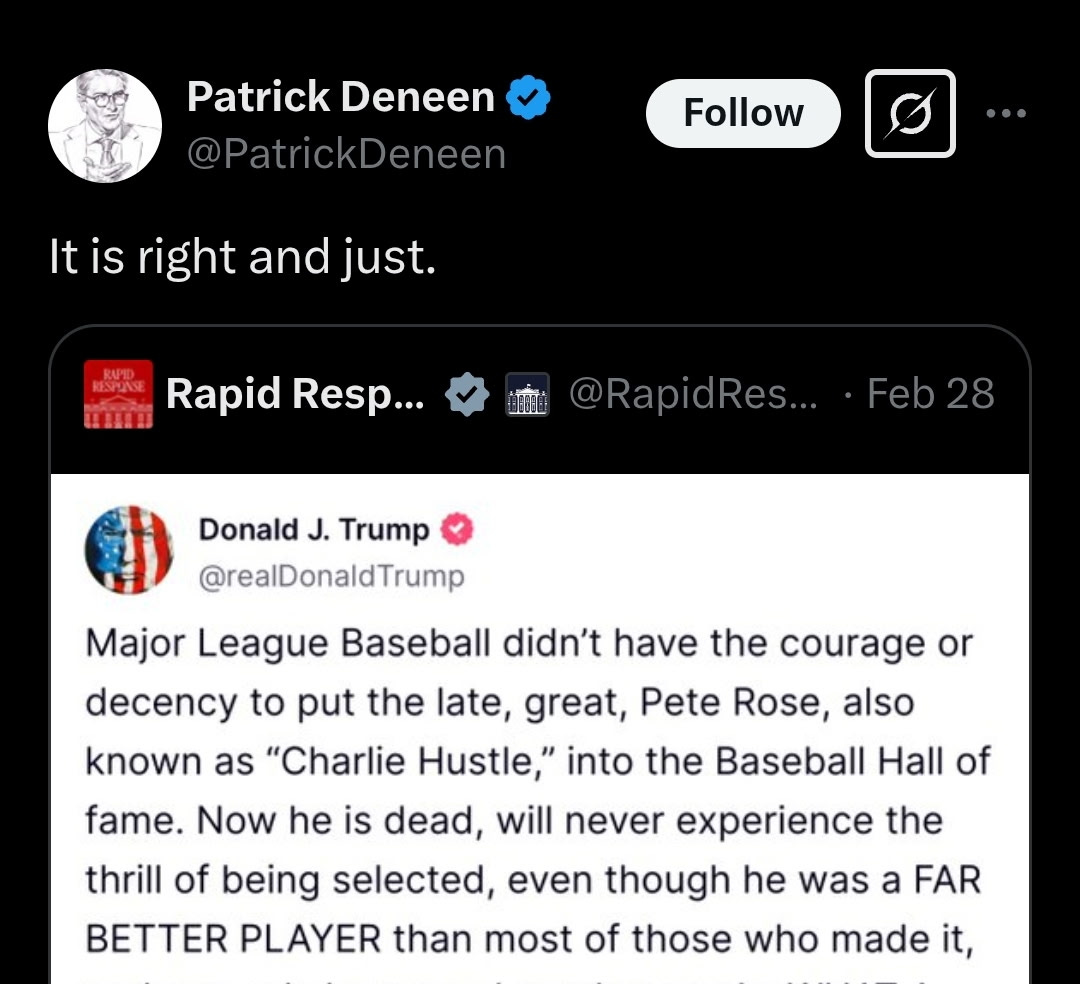

Meanwhile Deneen has moved closer to the policy objectives of Donald Trump. Deneen’s most recent book, Regime Change, complains of a grand progressive liberal conspiracy to attack and eradicate ‘whiteness’ in America, whilst calling into question the liberties attained by women under liberalism. Deneen has now started retweeting Trump’s posts with comments drawn from Roman Catholic liturgy to signal agreement: ‘it is right and just.’

This might be comical were it not for the fact that post-liberalism carries some weight in the second Trump administration. Significant policy advisors have been influenced by the work of Deneen, Dreher, and others. And some of the great officers of state would acknowledge the influence of post-liberalism on their thinking, including the Secretary of State Marco Rubio, and the Vice-President JD Vance.

Why did post-liberalism fail? The Benedict Option and Why Liberalism Failed caused such a stir of excitement when they were published in 2017/2018, especially in church circles. With the seismic events which took place over the course of 2016, here appeared two books which seemed to chart a way forward, diagnosing the present malaise with liberalism, and at least gesturing towards what would cause contentment and peace. Yet from the vantage of 2025, post-liberalism appears to be a tool for those who would replace liberalism with something more authoritarian.

Is it possible that amidst the critique and the negation, that both Deneen and Dreher have missed something significant about liberalism? By this, I wonder if negation of liberalism might have been tempered slightly be placing liberalism within the tradition from which it arose. I am thinking particularly of the work of Oliver O’Donovan, who is himself a very able critic of liberalism. ‘Late-modern liberalism…has followed the path of devaluing natural communities in favour of those created by acts of the will.’11 But somewhat provocatively, O’Donovan argues that liberalism has right of possession to the legacy of Christendom. While there is only one society ‘which is incorporated into the Kingdom of God and which recapitulates the narrative of the Christ-event, and that is the church’; nevertheless, modern society, having been confronted with the true society of the church, cannot just revert, ‘Having taken on the narrative form of the Christ-event, it cannot become unformed.’ Though O’Donovan cautions that ‘the worst, and the most characteristically twentieth-century, evils of political experience have been progressive.’12 With respect to possession, O’Donovan argues that:

‘[t]he liberal tradition, however, has right of possession. There is no other model available to us of a political order derived from a millennium of close engagement between state and church. It ought, therefore, to have the first word in any discussion of what Christians can approve, even if it ought not to have the last word. To think through the demands of the Gospel in unfamiliar circumstances, we must have understood its demands in familiar ones; and nothing whatever is gained by a posture of studied distance from the legacy of Christian political reasoning. If the church has to formulate, not an abstract statement of what might in principle be conceded to political authority, but a challenge to an existing political situation, then let it begin from the challenge the state has already heard and already responded to. We cannot simply go behind it; it has the status of a church tradition, and demands to be treated with respect.’13

O’Donovan qualifies this in two ways. Firstly, as a tradition, it must be interpreted and understood, not merely perpetuated. The liberal tradition is neither homogeneous or unchanging, but has evolved in the face of different challenges and influences: romanticism, rationalism, scepticism. socialism, etc. These challenges and influences both subvert and strengthen the Christian contribution to liberalism. Which means that liberalism does not carry authority in the theological sense, merely that it is organically derived from ‘the guiding principles of Christian society.

Secondly, tradition is not the same thing as revelation. Which means that it ‘cannot merely be assumed or posited.’ True liberty is only found in Christ’s victory over the nation’s rulers. Yet liberalism has shown itself throughout its history to be susceptible of not grasping the actuality of Christ’s victory in history.

There may be more continuity between Christianity and liberalism than we sometimes dare admit. But owning this truth allows to see liberalism for what it is. Speaking of the connections with liberal society, O’Donovan says:

‘This helps us understand as once how modernity is the child of Christianity, and at the same time how it has left its father’s house and followed the way of the prodigal. Or to paint the picture in more sombre colours, how modernity can be conceived as Antichrist, a parodic and corrupt development of Christian social order.’14

While O’Donovan cautions that a reading of a civilisation must be provisional and heuristic, he notes that true complimentary truths about liberalism can exist at the same time: it is a political order which ‘bears the narrative of the Christ event stamped on it’ and it can also display ‘the emergence of the pseudo-Christ of the last times’.15 Yet for O'Donovan, writing as he was in the mid-90s, the post-modern analysis and critique of modernity fails because it makes it sound like it is a fait accompli and so fails to present us with the decision between the two loves which made two cities.16 Did post-liberalism fall for the same interpretive mistake as postmodernity? Time will be the judge.

Patrick J. Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed, 2018: 2–3.

It is interesting to note that the American post-liberals seem to have minimal engagement with MacIntrye’s former colleague, Stanley Hauerwas. (Dreher quotes Hauerwas once in The Benedict Option, and has written several op-eds for The American Conservative that feature Hauerwas; Deneen not at all in Why Liberalism Failed. This is not necessarily an issue; though Hauerwas, who has been significant in shaping a political ethic rooted in pacifist and anabaptist thought, is a fellow traveller with the post-liberal theorists in critiquing liberalism. Hauerwas is well known for having said: ‘Liberalism is the presumption that you should have no story except the story you chose when you had no story.’

Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 1984: 263. Rod Dreher, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation, 2017: 16–18.

Dreher, The Benedict Option, 19.

Deneen, Why Liberalism Failed, 179.

ibid, 182–183.

ibid, 191–192.

ibid, 198.

ibid, 180–181.

Rowan Williams, ‘Preface’ in Geary and Pabst (eds.) Blue Labour: Forging a New Politics, 2015: ix–x. Taken from Joel Harrison, Post Liberal Religious Liberty: Forming Communities of Charity, 2020: 8.

Oliver O’Donovan, The Desire of the Nations: Rediscovering the Roots of Political Theology, 1996: 276.

ibid, 251–252.

ibid, 228-229.

ibid, 275.

ibid, 283.

See Augustine, The City of God, Book 14, Chapter 28. ‘Two cities have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; and the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self. The former, in a word, glories in itself, the latter in the Lord. For the one seeks glory from men; but the greatest glory of the other is God, the witness of our conscience. The one lifts up its head in its own glory; the other says to its God, “Thou art my glory, and the lifter up of my head” (Psalm 3:3).’

Great piece Matt! I came across it because it was mentioned by Adrian Vermeule. You have some interesting readers :)

Just wanted to thank you for this post. It made clear and accessible some trends in thought that I haven't put together, and things I have read with things I haven't read.