This is was a sermon I gave at St Oswald’s Haberfield on Father’s Day, September 2025, in a series called ‘Perfect Freedom’. The third in the series, titled ‘No Fear: Freedom in Experience’, the sermon zeroed in on Hebrews 2.14–15:

Since the children have flesh and blood, he too shared in their humanity so that by his death he might break the power of him who holds the power of death—that is, the devil—and free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death.

No Fear

Is there a concert that lives large in your memory? A musical experience that you’ve been unable to forget?

One that stands out for me was a performance at the opera house in 2015 by American indie artist Sufjan Stevens. Stevens had just released a new album, Carrie and Lowell, which came in the aftermath of his mother's death. You probably had to be there, but the concert was this mesmerising performance of music and light; Sufjan played through all these very personal songs about grief, without break for an hour. His song, The Fourth of July, ends with the line ‘We’re all going to die’. The way it was played that night, it was stretched out into a ‘violent thrashing crescendo’1, as the line was repeated again and again, and eight giant spotlights landed on different members of the audience each time the line sung, reminding us that death awaits us all; a modern memento mori – remember you are mortal.

Then he spoke; a little rambly, but eloquently, about the paradoxes of being human. ‘God has made everything beautiful in its time’ he said, quoting Ecclesiastes 3, ‘and set eternity in the human heart. And yet, he’s made us mortal. We all come from dust and we return to dust.’

And then something strange happened. The audience laughed. The mere mention of death and God, and the audience didn’t know how to deal with it. So they laughed.

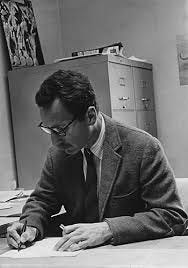

You might say that it was a very Australian reaction. We have a cultural trope about ourselves, that we don’t take ourselves too seriously. But in the 1970s the American anthropologist Ernest Becker made a similar observation to Sufjan Stevens. He said that:

[We are] literally split in two: Man [sic] has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever.2

This observation drew Becker to the conclusion that most human action is taken to ignore or avoid the inevitability of death. [What Dr Freud had called thanatophobia]. We are capable of splendid things, and yet death mocks all our pretensions and ambitions.

Our reading from the book of Hebrews would offer a similar diagnosis. Hebrews 2.15: Jesus died in order that he might ‘free those who all their lives were held in slavery by their fear of death.’

We’re in this series on Perfect Freedom. The fear of death – whether just the sheer dread of death, or the existential angst of dying – curtails our freedom. Instead of liberty, the spectre of death means we experience fear and slavery.

What are we to do about this? This morning I want to consider with you this three questions to help unpack this topic:

Where do we see slavery to the fear of death?

What has Jesus done about it?

What does that mean for us now?

Though before we go any further, I want to acknowledge that our congregation has had to deal with its fair share of grief over the last two years. And the first Sunday in September brings with it enough weight of grief: missing fathers; lost daughters and sons. This morning is going to be heavy, and it’s ok to feel that. I’ve learnt from experience that this community is one that is able to carry that grief together. If something comes up for you this morning, there will be people down the front here after the service to sit with, to chat and pray with you.

Where do we see slavery to the fear of death?

If you grow up here in Sydney, it’s possible to never think about just how privileged we are. The scale of wealth and resources we’re able to direct towards health care and research is unique in human history. I experienced this last year when my youngest daughter Anna was in neonatal intensive care for 81 days. She was so premature, that if she had been born 10 years earlier, she wouldn’t have survived. And my wallet experienced it because if it wasn’t for our health system, it would have cost me personally over $400,000 to pay for her medical care.

For all its faults and problems, the access we have to the healthcare system in Australia is incredible

And yet, death continues to strike with a 100% success rate. In spite of our relative peace and wealth,the 2020s have reminded us that death is closer to us than we might care to mention.

the bushfires and floods so many have been forced to endure,

the unabating threat of climate change which threatens to destroy us all

Rising global tensions, with the outbreak of war in Europe.

the pandemic that brought the possibility of death into our very homes on the back of a sore throat

The covid years are an especially poignant reminder of our proximity to death. For two years we limited the freedom of our movements to avoid bringing death into our homes. You never knew if you would catch it while you were ducking in to grab something at the shops.

Last weekend my Dad called me in the middle of the day. I can count on one hand the number of times dad has called me since I moved out of home, and usually it’s to tell me someone in the family has died. So I was a little surprised to see his number come up on my phone. Turns out that a road cyclist had been in a collision with a car on a route I very occasionally ride. Having seen the news, my parents panicked, and rang to check that I was ok, fully expecting that I was lying in the back of an ambulance somewhere.

It’s hard to escape the randomness of death.

It can be hard to find a rhyme or reason with the seeming randomness of death. A routine checkup which delivers dreadful, unexpected news. The driver who does everything right, but had no control over the other driver who had fallen asleep at the wheel.

It just so happened this week that many world leaders gathered in Beijing. While a lot of the coverage in Australia was focused on the attendance of a couple of former state premiers, you may have missed this conversation. As the leaders of China, Russia, and North Korea were walking down the street, the microphone picked up the unguarded Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin discussing how people could live to 150 and even become immortal. Putin suggested a regime of repeated organ transplants could stave off death. Part of me is not surprised to find dictators, who have used death and the fear of death to bend so many to their wills, discussing how they might cheat death.

For some people, what they fear is the unknown beyond death. That is what Shakespeare’s Hamlet is forced to confront. Who knows what's on the other side of death, what he calls ‘The undiscovered country, from whose bourn No traveller returns’. Hamlet doesn’t follow through with suicide because he dreads something after death – he fears being judged for the life that he has lived. For Hamlet the lack of return traveller from death means he’s not wanting to face the uncertainty of what death brings, we “bear those ills we have, than fly to others that we know not of”. Or as the poet TS Eliot said: ‘Not what we call death, but what beyond death is not death, We fear, we fear.’3 There is no hiding from the existential dread of what is to come in the future.4

Isaiah the prophet, writing 700 years before Jesus, describes death at one point as a great shroud or sheet that hangs over all of humanity, threatening to envelope us all. Death mocks all our ambitions and pretences. It’s unavoidable and inescapable, showing no regard for our background, our wealth or our education.

So what has Jesus done about death?

A little earlier in Hebrews 2, we read in verse 9, that Jesus has tasted death for everyone. By tasting death, Hebrews doesn’t mean Jesus sampled death in the same way that you might take little bites of samples as you prepare for a party. No, it means to experience something, to really come to know something cognitively or emotionally. Jesus didn’t taste test death, he dove straight into it. What Hebrews has in mind is the death that Jesus suffered on the cross, and his repose in the grave. But you might say that the whole of Jesus' life is a struggle with death.

Let’s briefly look at two episodes from the Gospels where Jesus experienced death prior to his own death.

There are, of course, the three people that Jesus raises in the Gospels: the daughter of Jairus in Mark 5, still lying on her death bed; the son of the widow of Nain in Luke 7, being carried on the way to his burial; and his friend Lazarus in John 11, who was enclosed in his own grave, having been buried for four days. It’s well known that in John 11 Jesus weeps as he meets with Lazarus’ grieving sisters, Martha and Mary. The shortest verse in the Bible, John 11:35: Jesus wept. Even the Son of God mourns in the face of death, because it intrudes into our lives.

Jesus wept.

What sometimes gets missed though is that on either side of verse 35, Jesus is twice described as being ‘greatly disturbed’, in verses 33 and 38. It’s the language used by Greek writers to describe the snorting of horses as they prepare to plough headlong into the enemy. In verse 38, when Jesus reaches the tomb, Jesus seethes with anger. Jesus is bellowing with rage. Jesus didn’t weep at Lazarus tomb because he was powerless to do something about it. He seethed with fury because death was the great enemy Jesus had come to destroy.

Death is not the way life is supposed to be, and our grief in the face of death acknowledges that. Many of the funerals I go to now refuse to talk about death, and try to hide away mourning. ‘It’s a celebration’ they say, ‘wear something bright’. But our grief in the face of death is real and right: death is not the way life is supposed to be.

Death tears loved ones away from us, or us from them. Death is hideous and frightening and cruel and unusual. It is an insult to the dignity which God has endowed us with. Death is our Great Enemy, more than anything else. It pursues us relentlessly through all our days.5

But the rage and the tears of Jesus in the story about Lazarus are not an isolated incident. Across his whole ministry, Jesus found himself in a confrontation with death. Maybe we miss them sometimes because of our 21st century living standards. But in the Gospels we see Jesus doing mortal combat with death.

In Mark 1, after teaching in the synagogue of Capernaum, Jesus retires to the house of Simon Peter and Andrew. Mark 1, verse 30:

Simon’s mother-in-law [that is, Peter’s mother-in-law] was in bed with a fever, and they immediately told Jesus about her. So he went to her, took her hand and helped her up. The fever left her and she began to wait on them.

We don’t think much of this because people recover from fevers all the time. I had a fever last week, yet you wouldn’t even know if I hadn’t mentioned it. But in the first century, without the access to the medicines that we now have, and the understanding of germ theory that we all benefit from, fever was the leading cause of death. When Jesus finds her, Peter’s mother-in-law is lying on her death bed. And Jesus overwhelmed the fever with his own life, such that the woman is healed. He took her by the hand, which feels so gentle but earthy at the same time. It’s as if she’s been pulled back out of the mouth of death itself. So restored is she, that she starts to provide hospitality to Jesus and the disciples.

Don’t miss what was at stake in this episode. This moment of healing in the Gospels is a sign pointing towards liberation, of pushing back the shroud of death which has enthralled humanity and trampled our experience of death.

Ultimately, it’s in his death and resurrection that Jesus broke the strong power of death over us. According to Hebrews 2, Jesus is the pioneer of our salvation. Another word for pioneer here is champion. Jesus is our champion, who doesn’t leave us to face death on our own. Jesus took on our greatest enemies—sin and death. In tasting death, Jesus experienced God’s judgment so that you wouldn’t have to. That’s why in Hebrews 2 verse 14, the writer says Jesus destroyed the power of death. Jesus rose from the dead because death no longer had any right over him. If the wages of sin is death, then Jesus had paid in full the penalty for sin by his death on the cross. Jesus takes away the sting of death by taking it on himself. He deals with our sin, our guilt, and our shame, so that even beyond death there is nothing to fear for those who trust in Jesus.

By his death Jesus has destroyed death. In rising to new life, death could no longer touch him. And he promises that new life to everyone who believes in him. That even though we die, yet will we rise again.

But let’s clarify for a moment what Christians mean when they say that Jesus rose from the grave.

When Christians say that Jesus is risen, we don’t mean that Jesus was still really physically dead, but the disciples had nice, warm and fuzzy feelings about Jesus. That makes the resurrection a mere metaphor, which would not have made any sense in the first century. That’s not what resurrection meant.

And when Christians say that Jesus is risen, we don’t mean that Jesus was somehow revived or resuscitated on that first Easter Day. Otherwise he’d still have a body susceptible to death. The Gospels record Romans soldiers going out of their way to ensure Jesus has died, thrusting a spear through his side and up into his vital organs. One thing you can say about the Romans is that they really knew how to kill people.

And when Christians say that Jesus is risen, we don’t mean that Jesus upgraded his body for a new one. Some people suggest that Jesus left his body behind in the tomb, and his resurrection was an ascension to a higher plane of existence. Or maybe he discarded his dead body, and assumed a brand new model. But each Gospel narrative records for us the continuity and physicality of Jesus’ resurrection body. The body that was buried on Good Friday was the same body that marched out of the tomb on Easter Day. It was able to walk and talk, eat fish and bread, and bore the healed wounds of the cross.

No, the only explanation for what happened on that first Easter Day is that Jesus burst through death, in one side and out the other, no longer subject to death or the corruption of his flesh.

Jesus has overwhelmed death with his life. He was so full of life and love, being the maker of all things, that death could not hold him. It was like a prison where he ripped the bars off. Jesus conquered death with his deathless love. The grave could not hold him because it had no right to him. And by tasting death, by knowing and experiencing death, Jesus has plundered death, freeing us from the fear and power of death. Freedom means no longer living in the fear of death.

Which leaves us with the question: What does that mean for us now?

After my son John died, one of the verses that was a comfort in the Moffitt household is the boast Jesus has in Revelation 1. He says in verse 17:

Do not be afraid. I am the First and the Last. I am the Living One; I was dead, and now look, I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades.

What a boast. Sometimes my kids take my car keys and like to boast that they now own the car. But they have no power to follow through on that boast. This is a boast that Jesus has the power and the authority to follow through on. In holding the keys to death and Hades, Jesus himself now holds all power and authority over death. Which changes death forever.

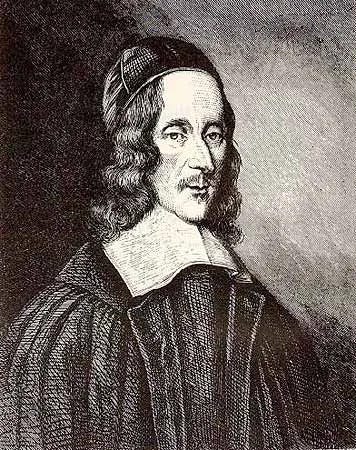

From his death bed at the age of 40, the 17th century English poet George Herbert wrote some of the most insightful lines about death. In the poem called ‘Time’, Herbert imagines himself meeting with the figure of time – who we would call the grim ripper – and Herbert launches his diss track on death. He mocks death for being slack and having a dull blade. But this is not mere bravado or denial from Herbert. It’s faith. Faith in Jesus’ power over death, for death’s blade brings not annihilation but new growth and eternity to the believer. Herbert says:

For where thou onely wert before

An executioner at best;

Thou art a gard’ner now, and more6

Where death had once been an executioner, it is now a gardener, planting Christians in the ground awaiting the resurrection of the dead. We await the day when Jesus returns, bringing with him new heavens and a new earth, a world where justice fits and righteousness is at home. Then shall all the dead be raised, and we shall see God face to face.

If Jesus holds the keys of death, if Jesus holds the power of death, then death is no longer something to be feared by those who follow Jesus. That’s why Hamlet was wrong. Death is not the undiscovered country. Someone has come back from death. Jesus Christ has destroyed the power of death, and opened a way for us through death to eternal life. When we grasp this by faith, we need fear darkness no more.

Which means that at the very least, Jesus has made death a safe place for all who now die in him as they await the resurrection of the dead.7 Rather than fearing death, in Revelation 14.13 it says that those who die in Jesus rest from their labours. While death remains a grievous presence in this world, death has lost its sting.

Paul says in Romans 8 says that we await the redemption of our bodies, and the arrival of a new creation. Maybe you feel that the older you get and the stiffer your limbs feel. You’re not quite as flexible as you once were, maybe the signs of your youth start to fade away – like me your hairline has beaten a retreat and thinned out. And besides all the joint and muscle aches there are more serious health problems you have to start attending to. The promise of the gospel is not one of slow and painful decline towards bleak extinction, but the beauty of resurrection morning, when we will share in Jesus’ glory.

It also means that in this life where we can expect many troubles and much suffering, there is always reason to endure suffering with joyful hope. What always strikes me about the letter of 1 Peter in the New Testament is the joy Peter feels and knows because of the resurrection. Writing to believers who are suffering for their faith, and being in the same boat as them, 1 Peter 1.3–6 says:

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! By his great mercy he has given us a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead, and into an inheritance that is imperishable, undefiled, and unfading, kept in heaven for you, who are being protected by the power of God through faith for a salvation ready to be revealed in the last time. In this you rejoice, even if now for a little while you have had to suffer various trials…

That would be sheer craziness if Jesus was still dead in the grave. A form of thanatophobia, the denial of death in the face of death. But since Jesus is risen and alive, there is joy, and even glory to be found in suffering now. That by no means diminishes pain and grief in the face of suffering and death. But what lies beyond the other side of death, the inheritance that is imperishable, undefiled, and unfading, is resurrection glory. That we will be raised like Jesus, with a body like his, no longer subject to decay and disease, sickness and corruption. A deathless body, a body made fully alive, in a world healed by the impairment of sin and death.

The fear of death is replaced by the hope of glorious resurrection. The worst that life can throw at you does not have the final word on your life. Through all the pain and the tears, we will be raised just as Jesus was raised. That doesn’t make grief any less real or painful. But if Jesus has the keys to death, turning it from executioner to gardiner, ultimately life wins.

Conclusion

So as we wrap up, let me ask you – are you able to identify the ways in which fear is holding you back from living in freedom? Are there ways in which the fear of death prevents you from being generous, or kind, or compassionate? Do you fear losing it all, and so shrink back from giving of yourself to other people? Are you looking for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come?

What is striking about the early church is how they embraced freedom from death. Unafraid of death, they lived lives marked by generosity and sacrifice. They gave generously to enable ministry to happen at home and on mission. They also stretched themselves financially to provide in real and tangible ways for those in need. And because they lived with a deep abiding joy and confidence in the resurrection, they weren’t afraid to make fools of themselves for Jesus. They shared Jesus with their friends and their neighbours, because they believed that he was not dead, nor a mere idea, but he was alive, and he was their Lord. They were even ready to lay down their lives for Jesus when the government demanded them, so confident were they that their lives were precious and safe in the hands of their Lord. They felt free to lose it all, in one sense, knowing that in Jesus they would lose nothing.

One writer recounts the strange ways in which the early Christians were different to their culture on this:

‘They would worship Christ among the bones of the dead. Believers would raise the bodies of martyrs in the air and parade them through the streets like trophies. At funerals they would gaze lovingly on the dead and sing psalms of praise over their bodies. Such behavior shocked their pagan neighbors. According to Roman law, the dead had to be buried miles away from the city so that the living would not be contaminated. But Christians placed the dead right at the center of their public gatherings’.8

There are probably public health restrictions that prevent us from reviving some of these traditions. But reflecting on these habits, and particularly the freedom of Christian martyrs in the face of death, the fourth century Egyptian bishop, Athanasius, wrote:

‘If you see children playing with a lion, don’t you know that the lion must be either dead or completely powerless? In the same way...when you see Christ’s believers playing with death and despising it, there can be no doubt that death has been destroyed by Christ and that its corruption has been dissolved and brought to an end?’

In a world filled with death, the early followers of Jesus met the reality of human mortality with a straightforward confidence in the ultimate triumph of life. Jesus tasted death, and instead of defeat, it’s victory, it’s freedom. By his death, we taste life.

Everything in this life is going to be taken away from us, except one thing: God’s love, which will go into death with us and take us through death and into his arms.

Let me pray. Lord Jesus, we thank you that you didn’t shy away from death, but plunged into the grave, and plundered death and the devil of their power. Thank you that we need not fear death. Keep is in your deathless love, and give us grace that we might trust you with our lives, and not fall back into the slavery of fear. We pray these things looking for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of theworld to come. Amen.

Antigone Anagnostellis, Vivid Live Review: Sufjan Stevens – Sydney Opera House (22.05.15).

Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death.

T.S. Eliot, Murder in the Cathedral.

There are other examples we could think of as well I am sure. Many of our great modern stories deal with form of thanatophobia. Tom Marvolo Riddle, otherwise known as the dark wizard Voldemort, split his soul several times (creating horcruxes, items in which his soul resides), in order to escape death. For all the bravado of Voldemort and his 'death-eaters', Voldemort killed and murdered out of his fear of death. JK Rowling left us clues of this with the anagram of Tom Marvolo Riddle – Voldemort – which means something in French like ‘flight of death’ or ‘theft of death’. Or you might consider the less familiarity we have we have with death compared to our forebears a century ago. The Australian Bureau of Statistcs estimate that most Australians died at home in 1925. Even if they didn't, many would have rested at home prior to their funeral and burial. In 2025 only 14% of Australians die at home. As a cultural feature, death has been medicalised, which means it has been outsourced to hospitals and aged care centres, and happens out of sight and out of mind. While much of this is due to the rapid increase of our living standards and medical treatment, it does mean we are less familiar with death than previous generations.

See Tim Keller, On Death.

George Herbet, Time.

A point made powerfully by Rory Shiner and Peter Orr in their book The World Next Door, in the chapter of Jesus’ descent into the dead.

Ben Myers, The Apostles' Creed: A Guide to the Ancient Catechism.